Evolution of the Mix (Tape)

It’s not easy for me to recall a time before creating “mix tapes” was not a favorite personal pastime. Now it’s called “curating,” I suppose, but back in the day it was simply “making a mix tape.” Once compact discs (CDs) emerged as a recording medium, I started calling them compilations and DJ mixes. Now they’re “playlists.” Over time, they’ve become easier to make and more efficient to distribute, but they have also, inevitably perhaps, become less personal. Or have they?

Stage 00: Vinyl Hunting

Vinyl records ruled, long before cassettes were practical for recording mix tapes. The earliest cassette recorders were simple things of dubious sound quality, used for recording silly skits or musical performances but impractical for creating high fidelity mix tapes. Some of my earliest memories literally revolve around LPs, the “long play” 33⅓ rpm vinyl records. When Dad brought home the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, if not on the day of its release (June 1, 1967), certainly shortly thereafter, it was a momentous occasion, filled with wonder. Our turntable regularly spun LPs by the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel, soundtracks of musicals—West Side Story and Man of La Mancha—while in the garage our portable 45 player played “Sugar, Sugar,” by The Archies, and other pop hits of the 60s.

I purchased my first LPs at K-Mart: Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon; Supertramp’s Crime of the Century; albums by Jim Croce and the Doobie Brothers. Later, I worked part-time during college in record stores in Santa Cruz and Santa Barbara. A good chunk of my meager paycheck disappeared, not surprisingly, to defray the cost of my expanding record collection. My collection grew in size and sophistication; Genesis and Peter Gabriel, Robert Fripp, Kate Bush, Talking Heads, Bob Marley. Frequent trips to record stores along Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue and San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury and North Beach neighborhoods, and later, Tower Records on LA’s Sunset Boulevard, yielded treasures from Africa and Brazil, and hard-to-find gems such as “Solid Air,” an import LP by Scottish singer/guitarist extraordinaire John Martyn.

Stage 01: Vinyl-to-Cassette

I wish I could recall precisely to whom my first mix tape was dedicated. For Dani, perhaps, or Jenny, or Francine, or some long-lost infatuation, during my early days of college. My first mix tapes were crafted on my friend Gus’s stereo system, the first recording system that I had access to which had decent audiophile quality. I met Gus at Cabrillo College and we both later attended UC Santa Barbara. Gus owned a Nakamichi, one of the best cassette recorders ever made, a Technics turntable, a Pioneer amplifier and an equalizer. Ray Dolby had introduced noise reduction, Dolby B, in 1970, based on his professional application that was used to record Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. Cassettes had finally become hi-fi.

My first mix tapes were strictly one-off creations. And, in all honesty, they were mostly about seduction. That is to say, they weren’t only about seduction—I made mixes as personal gifts for friends of both sexes—but the raison d'être was more often than not love or the pursuit of love. (Mix tapes were also about parties; more on that below.)

Someone was in my mind and for that person the mix was formed.

Dual Turntable: A steady and dependable workhorse

Creating a mix tape was an hours-long process, some times fashioned during a long, drawn-out chess match that certainly involved libations. Select an LP and place it on the turntable. Clean the black disc with Discwasher record cleaner, a special felt brush. Prep the cassette recorder to record and press the pause button. Drop the needle—carefully—on the chosen track and hope it lands with accuracy. Press record on the cassette. Listen for the end of the track. Push pause again. Lift the needle and carefully store the LP, or, if you missed the very end, reverse the tape slightly and find the end of the track.

Ending each side of the cassette required special effort. (There was usually slightly more than 45 minutes each side on a “90-minute” Maxell XL-II or XL-IIS, inevitably Maxell.) How much time is left? One could guess and choose an LP track most likely to fit the remaining space. More likely, I’d want to maximize play time and minimize “dead air” by first playing the remaining blank tape while timing it, reverse to the end of the last track, and find a track to fit precisely. While recording, I’d write each song down on a ruled legal pad and later, usually after “test-driving” the mix tape, write the tracks onto the label. Almost always, some theme or other was driving the mix.

Maxell XLIIS 90 minute cassette tape: the Gold Standard

The theme is critical, for the mix tape is a sort of narrative in time. Geoffrey O'Brien, poet and editor-in-chief of the Library of America, reportedly once called personal mix tapes “the most widely practiced American art form.” The theme can be very subtle: “Apocalyptica,” for example, a mix that I created from songs all subtly referencing lyrically the apocalypse.

During the early 1980s, the cassette format was becoming ever more popular. I never owned an 8-track player, although I remember one installed in one of the rides I used to run at the Santa Cruz Beach and Boardwalk, my senior year in high school, on which we’d play Van Halen while the kids spun around. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, 8-tracks were rapidly being replaced in car stereos by cassette tape players. Meanwhile, the Sony Walkman was introduced in the late 1970s. Early models were fairly expensive. The Walkman began to become quite popular for listening to music on cassette in the early 1980s as the price fell rapidly, from over $200 to $50 and even less.

I met Lisa at the record store where I was assistant manager, Leopold’s in Isla Vista, near the entrance to UC Santa Barbara. She came in looking for records—she was really into Fleetwood Mac and Stevie Nicks—and I was dancing around the store; we hit it off instantly. (Another great memory from Leopold’s was the time a Soviet Union swim team, at a meet at UCSB, came in the store, flooded with cash, wanting to buy anything, anything I suggested, so I turned them onto the Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, U2, and, obvious choices, the Beatles and Rolling Stones.) Lisa and I dated while we both attended UCSB and for a few years afterward. Lisa’s father was an international businessman in the toy industry—he licensed Peanuts for Charles Shultz—and he made frequent trips to Japan. At my request, he brought me back from Japan a new model called the Sony Walkman Pro WM-D6, an amazing portable recording deck that retailed for $300 in the US (a lot of money in 1982) but in Japan cost just over $100, and which possessed sound quality that rivaled the finest recording equipment of the time. Professionals used it for field recordings. I used it to record live concerts, and frequently to record mix tapes as well. At Lisa’s parents' house I also watched my first MTV, and first saw a videocassette player.

Sony Walkman Pro WM-D6: Mine still works but doesn't get much use these days

Stage 02: Compact Disc-to-Cassette

In the early 1980s, I returned to Santa Cruz and for a few years worked at an audio/video and appliance store—a family-owned store that predated Best Buy and other chains. I was able to purchase direct from Yamaha a quality system at a fraction of the retail price; a system that proudly or not, I still use to this day (or would use, I suppose, if it were not currently packed in boxes in my basement, but that’s another story, I suppose). A brand-new stereo component emerged in 1982–1983: the Compact Disc (CD) player. At first, most of the other sales guys and gals, let alone the general public, had their doubts about this new technology. The player was expensive (a decent player cost over $400 retail at the time, though my employee discount got me a top-notch Yamaha for about $150 or so). The availability of the CDs themselves was quite limited; new releases in the new format typically were delayed by months. But the potential for the mix tape was immediately apparent—although you could not record CDs at home (until the mid-1990s), you could record from CD to cassette with startling sound quality. Lacking the pops and crackles that sound irritating when recording from LP’s to cassette, it was also much easier to find, and commence, the desired track. For several years, my mix tapes compiled tracks from both CDs and vinyl, until the CD, relentlessly, took over as my collection of discs grew. Vinyl seemed on its death throes—it would have been hard then to imagine that vinyl would survive and today, even thrive (albeit as a hipster or “collector” item) and that CDs would soon themselves be obsolete. But let’s not get so far ahead.

Interlude: Hi-Fi and Hi Life

Another new format emerged around this time—one that proved briefly useful for extended mix tapes—the “Hi-Fi” VHS recorder. Hi-Fi VHS used additional band-width for audio to make movies sound better compared to normal VHS; crucially, you could record six hours of CD-quality audio on a single VHS tape.

Party mix? Yes, please. VHS Hi-Fi’s 6-hour length made it feasible to include Fela Kuti’s 12+ minute “Zombie” or Grand Master Flash’s epic “The Message” in the mix without using 1/3 of the Maxell’s 45-minute Side B. Long dance mixes, increasingly found on the new CD-single format proved no problem for this mix format; in fact, as long as the beat was present, the longer the better. Get ‘em on the dance floor and keep ‘em there, until they drop.

At many of my friends’ parties, I’d served as DJ, hooking up a turntable and a CD player, or two CD players, through a four-channel mixer. (DJ JDUB is my DJ moniker. As you probably know, if you’re going to be a DJ, a moniker is requisite.) I’d worked as a DJ in a couple of clubs and a couple times I’ve done it live on radio, including once spinning Brazilian funk and reggae on a station in México DF. But I’m not the kind of DJ that’s going to play “The Funky Chicken” at a wedding. My tastes were eclectic and didn’t lean toward top 40 or disco, but I knew how to get people to dance, to Talking Heads’ “Burning Down the House,” Peter Gabriel’s “Big Time,” Michael Jackson's “Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough,” and “Erotic City” by Prince, a 1984 B-Side that featured Sheila E in her recording debut. I liked introducing partiers to stimulating new tracks, such as New Order’s B-Side “The Beach,” or “7 Seconds” by Youssou N'Dour and Neneh Cherry.

A mix tape isn’t fundamentally different than a live DJ mix. Many a mix tape is introspective, but just as often I’m envisioning a party or a long, late-night road trip. As a live DJ, generally speaking, I want to get people to move, but this is not necessarily the case. I’ve manned the decks at a garden party where the object wasn’t to dance but create a vibe. I very nearly had the chance, once during Book Expo America (BEA), to DJ a party—tastefully of course—at the Library of Congress. Alas, no DJs allowed, string quartets instead. The main distinction is that there’s less room for error, it’s “live” after all, and in a live DJ mix I’m seamlessly blending one track into another, even layering one completely different track onto another (I don’t really “scratch,” but the “blend” is kind of an art form).

I was able to create a non-stop, six-hour mix by recording from CD-to-VHS Hi-Fi; it lacked the spontaneity of a live DJ performance but allowed me to bring less equipment and, more importantly, move around and even host the party. I’d map the ebb and flow of the party mix: gradually bring up the tempo as people arrive; here and there an experimental left-field track; tasteful, jazzy, world-beat during dinner; a pulsating section of reliable—if often unfamiliar to the audience—dance tracks; alternating selections of faster and slower beats; and a languorous, chill-out final hour. Perfect for Karen’s wedding at the “Hobbit House” in the hills of Santa Barbara, or for one of Gus’s blow-out parties, during the breaks when my band was not jamming, or at one of my own parties when being the host was also one of my duties.

CD-to-VHS Hi-Fi recordings proved impractical, however, for anything but the special party mix tape. Few people had VHS Hi-Fi at home, certainly no one had one in a car, and there was no such thing, for obvious reasons, as a VHS Hi-Fi Walkman. People listened to music on cassette, or on CD. Recordable CDs weren’t available until the mid-1990s but weren’t really affordable until around the turn of the century. My CD-to-cassette mix tapes, therefore were still one-off, personalized creations, but easier to make—perhaps an investment in time of two hours instead of three or four.

Interlude: Chain, Chain, Chain

Dual cassette players existed, but due to sound degradation from recording cassette to cassette I didn’t duplicate mix tapes in this manner. Nevertheless, sometimes my mix tapes got around.

In December 1989, a US-based golf-club manufacturer asked me to conduct a market research study on the Brazilian market for golf clubs. They wanted to know the size of the market and were also concerned about grey-market imports. My friend Juan invited me to his beach house on the coast outside of São Paulo for New Year’s Eve, a major holiday in Brazil and the festival of Reveillon. Juan lived in a beach town cum fishing village called Camburí. For the trip from São Paulo to Camburí, I was crammed into a Volkswagen Bug driven by Jorge, Juan’s brother-in-law, with Juan’s Italian cousin, Julio, and Rick, the American brother of Juan’s wife, Corrine, who was visiting from the US.

Jorge slipped a cassette into the Bug’s stereo and John Martyn’s classic song “Solid Air” started to play over the speakers. When the next song came on, another by John Martyn, I had a strange feeling, and by the third I knew absolutely that the cassette that was playing was a compilation of John Martyn tunes that I had created a year or so previous and had given to Juan. Juan, in fact, my friend and former Portuguese teacher, born in Argentina of Italian parents, had introduced me to the Scottish singer and guitarist many years ago in Santa Cruz, California; he himself had first heard Martyn in Milan, Italy. The cassette in the deck was a mix of classic Martyn tracks and rarities, such as live tracks and B-sides. Then things got even more interesting.

“Hey, Jorge, I actually made this cassette!”

“Really? Juan gave me a copy of it. It’s one of my favorites. I’m playing it so much it’s wearing out.”

Julio, from the back seat, exclaimed, “Juan made me a copy of this tape too; I have it at home in Milan.”

“I guess I’m the only one here without a copy,” muttered Rick.

So, cruising down a highway in central Brazil I hear one of my own mix tapes in a car driven by a relative stranger, and a third has a copy of the same tape.

In 1989–95 or so, during the early days of the Internet, I was involved in a couple of email listservs around fans of particular artists—the Lovehounds group which was made up of die-hard Kate Bush fans—fans who had to wait sometimes eight years between albums and abandon the idea of ever seeing her in concert. A group spun off of Lovehounds that focused on Tori Amos. The Lovehounds list distributed a chain of rare Kate Bush videos, German and Dutch TV appearances and the like. On the Tori Amos listserv, I helped organize a mix tape chain focused on live bootlegs of cover songs she performed in concert. We called it “Under the Covers” after one of her albums; it involved perhaps 50 people trading and compiling tracks. These mix tape chains involved a community of engaged fans who really didn’t know each other in person, outside of email interactions. Two of the members, however, visited me in California, one from Germany and one from Canada.

The CD age also inspired a cult of CD swappers, strangers sharing mix CDs through mix-of-the-month clubs or genre-specific groups.

Stage 03: CD-to-CD

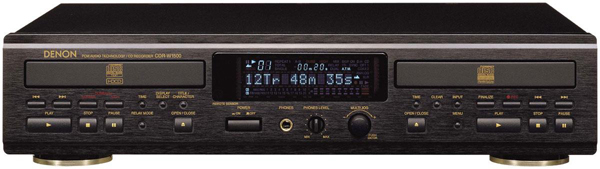

By the 1990s, CDs replaced audiocassettes as the most popular audio format. The first CD Recorders (CD-R), however, cost thousands of dollars when they first became commercially available. I received my first dual-deck CD, with CD recording in one of the decks, in 1996. It allowed me to record a live DJ mix through a mixer onto a CD master, or create a mix by recording tracks from CDs onto another CD, and duplicate the final mixes for friends. The recordable, “dual CD” deck revolutionized the mix—what previously remained largely a one-off, customized or personalized pursuit suddenly became reproducible with no loss in sound quality. But I didn’t go crazy with replicating discs.

Denon Dual CD Player/Recorder: High fidelity reproduction arrives

I’ve always followed a few simple but important rules: I don’t share recordings of an entire album—my mix tapes, and later mix CDs, smorgasbord diverse artists and styles, or, in some cases, compile rare tracks and highlights of a single artist or group. My overarching goal has always been to introduce friends into welcome but unfamiliar musical territory, so I’d avoid the obvious and try to bring to light emerging talents and overlooked gems.

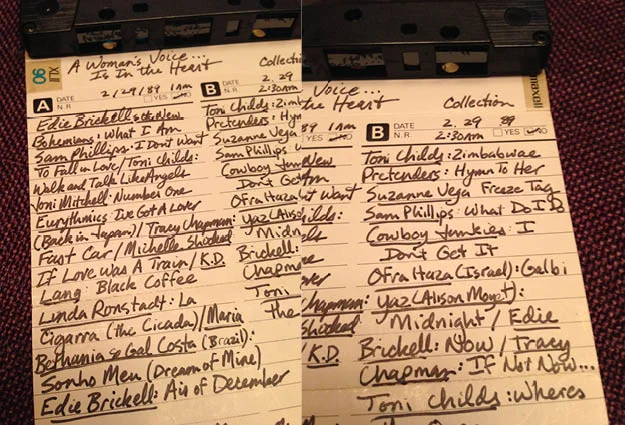

I’ve issued more than twenty different volumes over the past thirty years of my long-running series, “A Woman’s Voice… Is From the Heart.” The series started on cassette and later moved to CD; it introduced dozens of female singer/songwriters and interpreters before they became household names, such as Tori Amos, Sinead O’Connor, Sam Phillips, or Meshell Ndgeocello in the 1980s. Sia and Adele were early adoptions in this series, both of whom later hit the big time: I had included Sia’s song “Breathe Me” in 2004, more than a year before it was used as the theme song for the final episode of “Six Feet Under”; Adele’s voice graced the series in May 2008, long before she became a smash hit. Artists such as Courtney Barnett, Maika Makovski, Jenny Hval, or Torres made their debuts in the series this year. I love throwing in a rare “B-side” such as Sinead O’Connor’s “Damn Your Eyes” twenty years ago or, more recently, a relatively obscure Andreya Triana or FKA Twigs remix.

"A Woman's Voice ... Is From the Heart" collection (vol. 1), 1989

I started a tradition at BEA of bringing a selection of my mix CDs to dispense as gifts to my friends and business partners (often these were the same). I wasn’t familiar then with the concept of “personal branding” and this certainly wasn’t my intention, but over time, in effect, it did become a sort of calling card. Many of my friends and colleagues eagerly anticipated their annual mix; some told me it was their only way of discovering new music; many remarked how several months after receiving one of my mix CDs a track or two would become a major hit. “Somebody That I Used to Know” by Australians Goyte and Kimbra became ubiquitous nearly a year after I’d included it on one of my mixes. I’d pack no more than ten of a particular mix in my bag and would sometimes bring three or four different mixes, which I’d then target to particular individual’s tastes.

Stage 04: iTunes-to-CD

I’ve always been a fan of Apple computers: my first computer was an early Macintosh that I bought when I arrived in graduate school at UC San Diego, in 1988. I don’t recall precisely how much it cost (a lot) but I do remember it didn’t have a hard drive; it had two floppy discs and you needed to have the system disc in one slot and whatever program you were using—one at a time, natch—in the other drive. The first version of Microsoft Word for Mac must have taken about 60 bytes or so. I got my first hard drive six or eight months later—it had a whopping 1 megabyte which I figured would be enough hard drive space to last me forever; it probably cost me $400 or $500. Imagine!

Apple, of course, revolutionized music by introducing iTunes in January 2001, letting users copy album tracks from personal CD collections into their iTunes library. Now, you could carry a huge music library on your iPod—“a jukebox in your pocket—released in October that same year, or on your laptop computer; iTunes also facilitated, even encouraged, making playlists that could be “burned” onto CD. Two years later, with the introduction of the iTunes music store, you could purchase individual tracks, or albums. At first, digital rights management (DRM) software limited the number of CDs you could burn using tracks purchased from the iTunes store, and some record labels also experimented with adding DRM to prevent CDs from being copied, but these restrictions were later lifted.

Making mix CDs from iTunes was almost too easy, it was sooooo convenient to be able to reorder tracks in order to find the right flow, and burn a CD when needed. I respect copyright; I strongly believe it’s important to support musicians and songwriters. Although I wasn’t necessarily concerned with the well-being of record labels, neither did I consider them (entirely) rapacious, evil corporations only interested in huge profits. (As Tom Petty says in his foreword to Randall Wixen’s The Plain & Simple Guide to Music Publishing: “[It’s] a business that I’m not gonna call crooked, but I’m not gonna call it anything else.”) So I stuck to the rules—above—and limited the number of any one mix I’d give to friends. Needless to say, I never even considered selling my mixes or posting tracks on file-sharing sites.

For all its convenience, however, creating mixes on iTunes lacked the personal style and customized approach of recording one-off mix tapes onto cassette. It was a time-saver, without doubt, but it’s like the difference between a handwritten note and an email.

Interlude: The Death of Tower Records

The once-mighty Tower Records chain closed its doors in 2006, although some spots remained open overseas. Russ Solomon, Tower's founder, opened the first Tower in San Francisco in 1968.

For record collectors, and later CD collectors, Tower was paradise: it was possible to find nearly anything at Tower: rock, jazz, classical, rhythm and blues, but also obscure things: instrumental music, dance music before EDM became a popular genre, imported CD singles with rare B-sides, world music from the far corners of the earth.

I spent countless hours browsing Tower, especially the iconic Sunset Blvd location in Los Angeles, and my original Tower on Columbus in San Francisco, but I also made a point of visiting a Tower when traveling for business or pleasure to New York, New Orleans, Washington DC and elsewhere.

Tower collapsed because of its ill-conceived entry into online retail, trying and failing to compete against Amazon, from competition from big box stores—Costco, Walmart, and their ilk—from over-expanding into a multinational empire, possibly from Napster and other file sharing sites, and, perhaps more than anything, from becoming irrelevant, in an era impending death of the CD format and the too-late rebirth of vinyl.

Tower perished and a bit of me died inside as well. I rarely spend time in record stores these days. It’s just not the same.

Stage 05: Streaming Playlists, Spotify, and Beyond

Four or five years ago, Ed, one of my BEA buddies brought me, sort of as a gag gift, a cassette tape case with a flash drive inside, a mix tape memory stick. Yes, the CD has now become obsolete; new MacBook Pros don't even include a CD drive. A few years ago at BEA, instead of CDs, I did distribute a few—very few—mixes on flash drives (along with my track lists and liner notes, created in InDesign, on PDFs).

Now everything is in the cloud, and music is no exception. Music-streaming sites—Spotify, Soundcloud, Amazon Prime, et al.—are abundant. Many artists and labels complain about paltry fees paid by these services for streaming music, but some independent musicians have nevertheless made unexpected income from having their music discovered through streaming services.

Spotify allows me to legally put a mix online and share it with friends all over the world, through Facebook or Twitter, even allow anyone in the world, who subscribes or has a free account, to discover and enjoy. Since I’m kind of an obscurist, I usually find that not all tracks I'd intend to include are available. On my latest mix, “Stolen Dance,” a few obscure tracks and remixes were unavailable on Spotify, but no more than ten or so out of a three-hour mix, and it was easy enough to substitute other tracks or versions tracks; a small price for expediency.

Convenience rules. Personalization suffers. I suppose, though, I could create a Spotify playlist for you alone. And then share it with the world.

In the future, we’ll probably all be device free, with little chips implanted in our head, behind our ear, providing virtual reality and music and whatever else we desire. And I’ll only have to think up a mix, and beam it to you, wherever you are.